Redemptive Opportunities in Judea & Samaria

by Drayton Wade, Greg Spencer, James Smith, Mike Humphrey, & Jay Hein

Intro:

For thousands of years, a small semi-arid strip of land on the southeastern border of the Mediterranean known as Israel has been the center of competing religious, historical, and geopolitical claims for members of the three primary Abrahamic faiths. Numerous historical shifts have changed the control of this territory, each adding to the complex legacy and memory of its inhabitants. This legacy arguably begins with the Jewish conquest of the “Promised Land,” described in Judges of the Old Testament, and includes the destruction of the second temple by the Roman Empire in 70 AD, the Muslim Conquest of Palestine in 635 AD, the centuries of Christian crusades, and the long reign and later dissolution of the Ottoman Empire in 1918. In the modern context, however, no event has had as significant global implications for this region than the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948. This single event led to numerous wars between the Israeli populace and the many surrounding Arab Muslim states resulting in the effective diplomatic and economic boycott of Israel after the Arab League Summit of 1967 which proclaimed “The Three Nos”: no peace with Israel, no recognition of Israel, and no negotiations with Israel. Tragically, this situation left one group in particular, the Palestinians inhabiting the West Bank and Gaza Strip, in a state of limbo for over five decades, with dire economic, humanitarian, and political consequences.

Yet, despite the complex, scarred, and overlapping cultural and historical legacy of Israel and Palestine, and despite the numerous failures of foreign aid and political dictates to reach a lasting solution of peace and prosperity in the region, opportunities are arising that demonstrate how co-prosperity and the laying of a foundation of trust can be achieved through an unlikely source: the marketplace. This paper sets out to describe the opportunity of business to help heal millennia of cultural wounds through the creation of an integrated (Christian, Jewish, and Muslim) emergent economy in the West Bank of Palestine (also known as Judea and Samaria). This white paper, jointly authored by the CEF Middle East Strategy Group, will first at a high level describe the present situation in the West Bank by contrasting it with that of Israel proper. Second, the question of “Why Now?” will be addressed, outlining the unique factors creating the opportunity for the development of an emergent, integrated economy in the third decade of the twentieth century. Lastly, the paper will outline “What Can I Do?” by providing as examples two areas of particular opportunity where CEF members and other investors/entrepreneurs/philanthropists could be involved. We will also provide case studies of two CEF members using commerce to generate returns and see prosperity and the love of Christ flow throughout the Holy Land.

A Tale of Two Territories:

Standing up to eight feet high in some places, the Israeli West Bank Barrier, built during the Second Intifada in 2000, effectively separates the predominantly Jewish “Israel” from the primarily Arab “West Bank.” The controversial wall, while documented to have a significant effect on decreasing violence in the region, divides two territories starkly contrasted in terms of human development, economic prosperity, and political stability.

On the “Israeli” side of the wall, there is one of the most remarkable economic stories in modern history. Israel, a new and at first primarily agrarian state built by poor refugees from across Europe and even parts of Africa and the Middle East (Ethiopia, Egypt, and Yemen predominantly), now stands as the most prosperous economy in the Middle East, despite limited natural energy resources. Hailed as a “Startup Nation” in the best-selling 2009 book of the same name, Israel, in the early 2000’s, produced more tech companies listed on U.S. stock exchanges than any country in the world outside of the United States.[1] Israel, today, has some of the highest education rates in the world at 83%, compared to the OECD average of 67%, and is home to thriving technology, bio-medical, and renewable energy industries. All three of these industries are poised to exponentially grow throughout the twenty-first century.[2]

On the Palestinian side, a very different situation exists. The economy in the West Bank is largely dependent on foreign aid, primarily from Europe, The United States, and Arab countries in the region. The economy is dominated by public service jobs provided by the Palestinian Authority and a significant SME sector. Though education levels are strong throughout the West Bank, unemployment, especially youth unemployment, is terribly high at nearly 50% in mid 2018,[3] with GNI per capita relatively stagnant. The specific challenges affecting a few of these sectors in particular (SME, Advanced Manufacturing, and Technology) will be explored in greater detail later, but the drastic disparities between life on each side of the wall create a cauldron for political distrust, anger, radicalism, and violence.

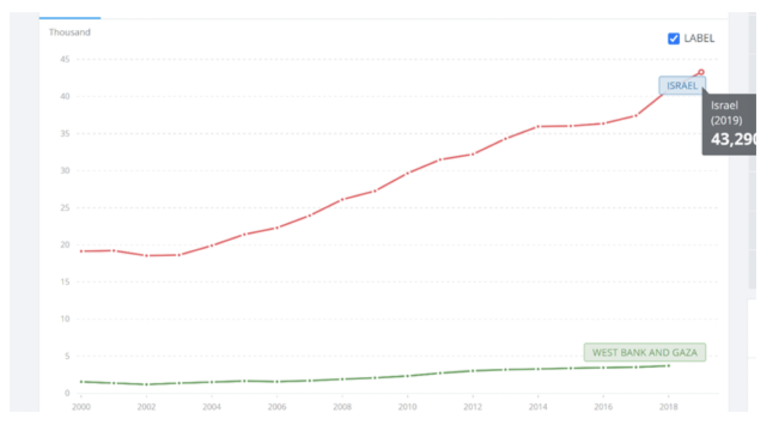

To understand the breadth of the gap between the Israeli and Palestinian economies, it is helpful to consider a few key development indicators. At a gross level, Israel’s overall economic production per capita is vastly greater than the West Bank & Gaza Strip, and the gulf between the two is growing rapidly. As illustrated in the chart below, over the last twenty years, Israel’s economy has grown 126% to almost $45,000 GNI per capita, while Palestine’s economy remains less than $3,710.[4] COVID has additionally disproportionately affected the West Bank with a contraction of its GDP by 7.6%[5] compared to only 4.1% across the Middle East and Central Asia region,[6] thus causing an economy that is highly dependent on foreign aid and public service jobs to be teetering in many respects.

Why Does This Matter?

Along with the historical and biblical significance of the Holy Land for Christians and the broader geo-political consequences related to gulf-competition between Iran and GCC states (which this paper will not address), the significance and importance of flourishing in the West Bank has far greater consequences for Christians around the world. The plight of the Palestinian people has been a major destabilizing factor in the broader region surrounding Israel, often used as a rallying cry for Islamic terrorist organizations including Hamas, Hezbollah, Islamic Jihad, and others. Potentially even more significantly, the undecided status of the Palestinian refugee question inflicts severe economic ramifications on the broader regional market at large. The boycott of Israel by the Arab bloc has prevented the development of a strong economic market in a region with abundant natural resources and geographic significance for international trade between Asia and Europe. Even recently, the boycott has limited exportation to MENA economies of Israel’s bio-medical and tech sectors, notably during a time when many of the wealthy oil-based Gulf States are desperately trying to diversify their economies. It can be argued that the plight of the Palestinian people in the West Bank and Gaza strip, and subsequent boycott by the Arab nations, has affected the development and flourishment of 300 million Arabs by preventing the development of a true regional market.

As Christian businessmen and women, we should lament the lack of development in this region, its associated social and humanitarian effects, and the missed opportunities for the market to bring about human flourishing. Likewise, as we are called to love the ‘least of these,’ our hearts should break over the decades of suffering that many of our Jewish and Arab brothers and sisters have faced due to the languishing geo-political and socio-economic conditions mentioned above. Thankfully, recent events have opened opportunities for a change in the stagnant status-quo, for market opportunities to be seized, and for driving innovation, prosperity, and hope to millions of people living in this historic region. This “opening” offers the chance for the disciples of Christ to minister both in word and deed to the inhabitants of the Holy Land and Arab Gulf by building a market of thriving businesses and deep-rooted relationships that transcend historical legacies and differences.

The Current Opportunity:

“The digital economy can overcome geographic obstacles, foster economic growth and create better job opportunities for Palestinians. With its tech-savvy young population, the potential is huge. However, Palestinians should be able to access resources similar to those of their neighbors, and they should be able to rapidly develop their digital infrastructure as well.” –Kanthan Shankar, World Bank Country Director for West Bank and Gaza

Until 2020, only three states in the region surrounding Israel had formally recognized the state and opened their doors to trade and mutual prosperity: Turkey, Egypt, and, lastly, Jordan in the early 1990s. Numerous security and political attempts to solve the situation had failed. However, a monumental shift changed the trajectory in a positive direction on September 15, 2020, when the United Arab Emirates signed the now named “Abraham Accords” with Israel, opening the door to trade, diplomatic relationships, and exchange with not only a wealthy gulf state but also a global center of finance and trade. Soon after, Bahrain, Sudan, and Morocco followed suit with others expected to follow, most notably a potential reconciliation with Saudi Arabia. While the long-term political ramifications remain to be seen, the economic impact creates numerous opportunities for investors, corporations, and startups to engage in what is likely to be a quickly developing market.

Coinciding with the macro-economic changes for Israel, the West Bank, and the Western Middle East, a unique set of collaborations is developing to foster “integrated” opportunities for prosperity between people of multiple faiths in Israel and the West Bank. An amalgamation of investors, including Sir Ronald Cohen of Portland Trust and Michael Milken of the Milken Center as well as organizations including Sagamore Institute, is looking to help develop startups and small businesses not only with high growth potential but also creating new markets entirely. Research by Harvard professor Clayton Christensen, well-known author of The Innovator’s Dilemma, suggests that investment in businesses with “market creating innovations,” targeting previous non-consumers or markets of non-consumption, is a core means of nation-states rising out of poverty and into prosperity.

“…every successful new market that is created, regardless of the product or service being sold, has three distinct outcomes: profits, jobs, and the most difficult to track but perhaps most powerful of the three, cultural change.”– Clayton Christensen[7]

With the recent Abraham Accords and hopeful future normalization between more Arab states and Israel, entrepreneurs and investors in Judea and Samaria now have the opportunity to provide such innovations to a market of hundreds of millions of Arabs in rapidly modernizing economies, many with categories previously untouched. While many such industries for “market creating innovations” will become possible in the coming years, including areas of tourism, trade, logistics, and finance, the remainder of this paper will focus on the opportunity for impact investors, entrepreneurs, and business leaders in two industries: Technology Services and Advanced Manufacturing. Each is well-positioned to create or cater to new markets, helping to provide prosperity through local jobs and cultural exchange.

Technology Services

Unsurprisingly, one of the biggest industries of opportunity for the West Bank in this emergent economy is the specialty of its neighbor Israel. Technology services have a tremendous amount of potential to bolster the economy of the West Bank, creating well-paying, meaningful jobs while boosting the quality of life for local inhabitants at the same time. While many industries are severely limited by the security constraints that limit movement in and out of the territory, technology is far less affected, needing only sufficient, undisrupted connectivity. The proximity to Israeli entrepreneurs, operating in arguably the world’s second most significant technology hub, enables ripe interaction and the exchange of ideas. The recent Abraham Accords and the expected emergence of a regional market among the Gulf Arab states and Israel removes the economic boycott barrier and opens the doors for the labor force of the West Bank to provide technology services to the rapidly digitizing Arab States.

Tech Market Opportunity

Prior to the recent Abraham Accords, Israel’s entrepreneurs faced highly-limited market opportunities in the Middle East due to the economic blockade of Israel. Because of this, the vast majority of Israel’s exports, over 50% of which fall in the technology sector, now go to Europe and North America. As such, the total addressable market for these innovative companies remained constrained, with the associated effect of limiting the total amount of labor needed to sustain development, support, and other technology services. The Abraham Accords have drastically changed the market opportunity for Israel’s tech sector, as these businesses will now have access to the more than 500 million people living in Arab League countries who are simultaneously coming online with high levels of digital engagement. For example, their citizens have some of the highest digital rates in the world including e-commerce usage, hours spent online daily, and smartphone usage. Internet usage in GCC states grew 2000% from 2000 to 2012.[8] The demand for technology and supporting technology services in these opening markets is far more rich than many would presume. The Arab world has very high levels of digital engagement and are buoyed by significant capital deployed into this sector by Gulf State sovereign funds, which are rapidly attempting to diversify their economies away from a total dependence on petrochemicals, such as Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 fund.

As technology companies grow, the need for skilled but low-cost back-end labor grows significantly. Traditionally, this has been largely supplied through the outsourcing powerhouses of South and Southeast Asia. However, demand from technology customers and even non-technology customers looking to outsource IT services has shifted in the last decade with a greater focus not only on low cost, but also for “nearshore” pods who share culture, language, and timezones with their respective customers. Evidence of such can be seen in the vast growth in the technology-services sector in LATAM countries, such as Colombia, and in moves by technology service powerhouses like Infosys in “localization,” opening service-hubs in various LATAM and US cities to support the American market.[9] As the Arab-Israeli market emerges, demand for local, or “nearshore,” technology resources will increase significantly in order to support not only Israel’s vast technology sector but also the growing financial, trade, and energy hubs of the Arab world. However, opportunity alone will not lead to the development of a technology-services sector in the West Bank. Experience shows that certain conditions are required for a services hub to emerge.

Requirements for a Thriving Technology-Services Sector

Connectivity is only one of the conditions needed for a successful technology-services industry to develop. In addition to access to digital networks, service providers identify the following conditions as primary considerations when looking at different outsourcing locations:

Education: Is there a substantial education system able to produce critical thinking and problem solving among its students?

Language: Are the language skills of the average worker commiserate with the typical firm’s customers?

Affordability: Is the typical wage for a high-skilled job within a range that would still support an outsourcing model?

Labor Market Size: Are there enough workers, who are either trained or who could be reasonably trained, to provide the particular technology services in demand?

Risk: What are the considerations regarding rule of law, transparency, nepotism, political violence, systemic financial risk, etc.?

To date, the West Bank meets some of these conditions, while others, most notably risk, are still question marks in order for the technology-services industry to thrive. Palestinians pride themselves on high rates of education, with universities both in Israel and in the West Bank providing many opportunities for enterprising youth. Likewise, language is a strength for the West Bank. As a regional market develops with increased trade among Arab states and Israel, the Arabic language will provide a differentiated edge. The average hourly wage of $4 would certainly enable firms to provide above-average pay for skilled labor and still be competitive in a “nearshore” type offering. A total labor force of roughly 1.3 million people is certainly a small labor market, but with 86% of working men possessing advanced education, the pool of potential talent for high-skill, outsource labor is larger than one would initially assume.[10]

According to a 2018 World Bank’s report, “Tech Startup Ecosystem in the West Bank and Gaza,” plenty of investible tech startups exist, but the primary issue is managerial experience, which must be supported by foreign investors willing to support entrepreneurs in mentorship roles.[11] Impact investment in such technology services and tech startups not only has potential for return due to the developing regional market and the demand generated by Arab states but also can help lead to the development of the West Bank itself, improving human quality of life outcomes and building relationships across ethnic lines.

“Stimulating the emergence of an effective entrepreneurial ecosystem offers one of the most promising mechanisms for creating such [vertical] progress, precisely because the nature of Palestinian economic challenges cannot be addressed through incremental gains.”- The World Bank[12]

Impact Investment Opportunity

Thirty-five miles from Bethlehem, Tel Aviv is home to the highest number of start-ups in the world behind only Silicon Valley.[13] As real estate prices are pushing people out past the “green line,” even Samaria and parts of the West Bank are becoming a piece of the commuting zone for a start-up nation with talks of annexation.[14] Despite the economic successes of Israel, Palestine has seemed to be left behind. With the introduction of the Abraham Accords and focus of impact investors on the region, several of the factors necessary to drive impact investment into Palestine are taking shape.

Requirements for a Thriving Investment Sector

With the booming economy of Israel only a short distance from Palestine, the issue is not necessarily lack of exposure to start ups, economic development, and funding, but, instead, other pieces are missing. All together, these missing pieces form an investment ecosystem that creates sustainable economic growth through the symbiotic relationship between businesses of all sizes and investors as well as the communities in which they operate.

Key pieces necessary for entrepreneurs to participate in this ecosystem include:

Mentoring: Are there resources in place (i.e., mentors, startup hubs, accelerators, etc.) to help entrepreneurs navigate growth and scale their businesses?

Capital: Is there sufficient investment capital flowing into the region to grow new ventures?

Multinational Corporations: Are multinational corporations present in the area to create jobs, pull in periphery industries, and drive a regional development?

Thus far, these conditions are improving in Palestine as spillover from Israel pushes investment further out in the region and the initial cohort of investors commit their skills, capital, and networks to the region.

Conversely, to reach the inflection point of continued and sustainable growth, investors require the following pieces:

Qualified Startups: Are there startups with skilled founders building a defensible business model?

Pipeline of Deal Flow: Is there an adequate amount of companies meeting the proper investment criteria to warrant a focus on the region?

Network of Other Investors: Are other investors investing in the region in order to co-invest in deals and create a broader investment ecosystem?

Signs of Progress and Opportunity

Initial investors in the region have seen success in Israel, and similar success is seen in the West Bank, although it is in the early stages. A nearby case study that created the ecosystem necessary to drive investment in the region involves Jerusalem-based OurCrowd, which operates as a platform for accredited investors and institutions to invest in startups and venture funds. Since 2014, OurCrowd has participated in over 138 deals in Israel and is ranked by Pitchbook as Israel’s most active VC fund.[1] The investment platform extended its impact on the region through its Global Investor Summit, which brings together VC leaders, multinational corporations, institutional and individual investors, entrepreneurs, and other professionals. Its event in 2019 saw 18,000 registrants and a number of top-tier speakers, which has historically included Sir Ronald Cohen, an active impact investor in the region.

In 2003, Sir Ronald Cohen co-founded the Portland Trust with Sir Harry Solomon with the aim of developing the Palestinian private sector and reducing poverty in Israel through social investment and social entrepreneurship.

As institutions such as The Portland Trust bring growth to the region, the Abraham Accords have only accelerated this process by delivering committed capital. The Abraham Accords and related peace agreements have ended decades-long boycotts of Israeli businesses and products by Arab states.[15] On the heels of this agreement, OurCrowd CEO and Founder, Jonathan MedVed, announced a $100m partnership with UAE’s Al Naboodah’s Phoenix, stating, “The sand curtain that existed between Israel and the Gulf has now come down, and there’s no rebuilding it.” OurCrowd is looking to sell Israeli products to the Gulf and to build new ones with Emirati partners to establish joint long-term investment platforms beneficial to both sides. There are also initial discussions around building an R&D center.[16]

Emirati entrepreneur Sabah Al Binali said, “Everybody is just looking at Israel and the UAE as endpoints, looking at domestic demand in one country as total demand from the other, but Israel and the UAE are complimentary global trade partners; Israel has comparatively stronger links to the Western world, while the UAE comparatively to East Asia.”

Other pieces of the puzzle continue to fall in place for the West Bank, such as the Milken Innovation Center, Israeli-Palestinian Business Accelerator, and Integrated Business Roundtable, taking significant steps to continue the development of a sophisticated investor ecosystem.

In October 2020, the Integrated Business Roundtable held its inaugural pitch competition which showcased two promising West Bank startups: an energy storage company and an AI-based wellness platform catering to the traditional Arab diet. After a brief presentation by the entrepreneurs, the judges awarded the companies 500k shekels each to fund their next stage of growth. Following the pitch competition, both startups have been connected with other investors, corporate leaders, and vendors that have further assisted their growth and will benefit not only from outside capital but also from the expertise and networks of investors and the organizations mentioned above.

Similar to the examples above, as organizations lay the groundwork to begin building out a thriving investment ecosystem in Palestine, there are numerous opportunities to have an impact by executing a “pull” strategy of development (in which the necessary institutions and infrastructure are pulled into a society once the markets demand them). We believe that the next piece of development involves multinational corporations taking a stake in the region by developing a physical presence.

Cisco has been doing exactly this since 2008, outsourcing projects from its Israeli office to three companies in Palestine Territories. Cisco ultimately contributed $15 million to the Palestinian economic development, including millions of dollars in incubation, venture capital, and equity funding for ICT companies as well as a capacity building program for entrepreneurs.[17]

Advanced Manufacturing: Industrial and Special Economic Zones

Industrial and Special Economic Zones are concentrated geographic areas designated for specific priority industries or manufacturing that receives investment incentives from the local government, including reduced tax rates, established facilities, access to export services, and others, to attract foreign investment. These zones can provide critical infrastructure in developing economies to increase local production capacity, reduce dependence on imports, generate employment, and spur economic growth. China has leveraged this model throughout the world as part of its Belt and Road Initiative, which has been a centerpiece of its foreign policy that has created special economic zones and industrial parks in 70 developing countries across the world to lower transportation, labor, and overall costs. Initial development of these zones has been completed by both the Israeli government and the Palestinian Authority through its Investment Fund, though additional supporting infrastructure must be developed for the Palestinian zones, in particular, to thrive.

There are 15 Israeli-run industrial zones in the West Bank that provide Israeli production capacity and Palestinian and Israeli jobs and that contribute to both economies, though more heavily to the Israeli economy. The Palestenian Investment Fund has established two Industrial Zones, Tarqumia, located near Hebron, and the Jericho Agro Industrial Park (JAIP), just 30 kilometers from Jerusalem, both of which are operational and currently house 10 active companies with another 30 companies signed to establish operations in the near future. Tarqumia is designed to be a bonded area to facilitate the export of goods from Palestine, while the JAIP is touted as a sustainable development project designed to be Palestine’s largest industrial city focused on agro-industrial projects.

Palestine’s Industrial sector is under capacity and has been in a slow decline since the mid-1990s. Its contribution to its GDP has fallen from over 22% in 1994 to roughly 11% in 2018. In addition to falling industrial-sector contribution, production capacity of existing firms has fallen to 50%. This decline is primarily due to the restrictions on Palestinian businesses which affect both access to raw materials for production of goods and a lack of access to Israeli and other regional markets.[18] Palestine remains a challenging place to do business, with its consistent ranking in the bottom quartile of the East of Business ranking. However, with the passing of the Abraham Accords, many hope that increased access to domestic regional markets as well as leverage of the underutilized and highly-educated labor force can create a boom of employment, export, and overall economic growth. In addition to increased access to regional markets, one of the government’s top priorities is boosting industrial production and contribution to the national GDP.

To achieve this, the Palestinian government is updating and increasing its investment incentives, improving and easing regulations on business, increasing access to credit facilities, and intensifying its strategy for developing economic clusters or geographically concentrated groups of similar businesses to achieve economies of scale.[19]Lastly, the Palestinian Government’s Recovery Plan aims to create conditions for stronger exports and a more resilient local supply chain through tax incentives and regulations on imports from Isreal.

Post Covid-19, Palestine can build a resilient, localized manufacturing base if it can address these primary barriers:

Stable supply of electricity, water, and communications to Industrial and Special Economic Zones

Executed policy reforms and investment incentives

Israeli government support and facilitation of access to imports, transportation, and regional markets

If these critical barriers cannot be overcome, then Palestine’s industrial output is likely to continue its decline, and resources would be better allocated to developing a robust tech ecosystem that leverages local talent and is insulated from the logistical and regulation barriers holding back capacity.

Case Studies:

This paper has provided ample evidence of the macro-economic and theoretical opportunities for Christian entrepreneurs, investors, and business leaders to take part in the development of prosperity in the emergent economy of Judea and Samaria. But, all good theories need to be tested. The following two examples, one of an investable, well-positioned startup and the other of a way a CEF member became involved in the region, demonstrate how CEF members reading this paper could become involved in this emergent market should they feel called to do so.

The following example, stemming from the recent Integrated Business Roundtable Start-Up Showcase, provides a strong initial data point of such opportunities.

Startup Case Study

One promising startup arising in the West Bank is a wellness mobile app based on a dietary points system designed specifically for the Arab world. Led by an unlikely partnership between a former American-Israeli corporate lawyer/investment banker and a Palestinian nutritionist, this startup is well-positioned to cater to the highly digital Arab world while tackling one of the biggest healthcare challenges in the region. Noticing the pervasive problem of obesity and diabetes among women in the Arab World and the drain this problem has on public healthcare funding, these two entrepreneurial women set out to create a “Market Innovating Solution” that is accessible, affordable, and effective. Through their mobile app containing a weight-watchers-esque points system, curated recipes, and algorithmic dieting suggestions, this startup helps its users live a healthier lifestyle and manage or decrease the likelihood of diabetes. Diabetes is a massive problem in the Arab world and is one of the leading contributors to public-sector healthcare costs for GCC states.[20] As a part of the technology-services business, this multi-ethnic startup has a pathway to significant growth due to market demand and conditions. It will provide jobs in the West Bank that will help develop the local economy, and it will help improve the health of Arab men and women throughout the region, which should decrease the strain on the public sector.

CEF Member Case Study: Jay Hein

As noted above, many opportunities abound for entrepreneurs and investors around the world to participate in the emergent economy of Judea/Samaria. One such example comes from CEF member Jay Hein below:

At Sagamore Institute, I’ve been involved in policy development and business solutions to the world’s biggest problems for decades. And, there is no problem bigger than the Israeli / Palestinian conflict. Until recently, my interest in Israel was bifurcated. Professionally, I was a champion of the state of Israel due to its vital role as America’s essential ally in the Middle East. The bilateral relationship was forged during the Cold War as Israel served as America’s military and intelligence asset in the Middle East. Today, the partnership has been accelerated by Israel’s economic innovations.

Personally, I have been deeply interested in God’s love for the land and all the ways heaven has met earth on the hills of Judea and Samaria. Of course, Gen 12:13 sets the scene: “I will bless those who bless you, and whoever curses you I will curse and all peoples on earth will be blessed through you.”

Thanks to the Integrated Business Roundtable, I have been able to unify these two interests. Bigger picture, it’s both humbling and exciting to live in a time in history when three forces have converged: the state of Israel was re-established after a couple-thousand year dispersion; the biblical heartland of Judea and Samaria is experiencing an economic renewal; and the Abraham Accords have ushered in a new era of Jewish and Arab collaboration. The opportunity to bless Israel through impact investment and business development is one of my life’s great privileges. And, to join forces with faith-driven colleagues at the Integrated Business Roundtable is one of my life’s great joys.

Conclusion:

As many in the CEF community are well aware from first-hand experience, investing and building businesses in the developing world is never easy and is often highly dependent on an alignment of resources, knowledge, networks, market conditions, and timing. This paper has made the case that these criteria are falling into place within the Holy Land, presenting Christians with the unique opportunity to be the hands and feet of Christ in Judea and Samaria through participation in the development of an emerging economy. The Abraham Accords combined with the efforts and investments of organizations and high net-worth individuals such as those mentioned above have produced an opening for commerce in partnership with philanthropy and government to begin doing what billions of dollars of foreign aid have failed to do for Palestine — create a thriving society for human flourishing of all ethnicities. Christian businessmen and women have numerous avenues through which to participate in such an opportunity, either through investing, partnering with key capacity building organizations on the ground, or using their considerable expertise and knowledge to mentor and connect hard-working entrepreneurs in the region. The potential for spiritual and financial returns abounds, prompting those of us who are interested in seeing peace in the Holy Land to ask: How might the Lord call our capital, our time, and our hearts to be a part of this unique redemptive time in the land where Christ and our spiritual forefathers walked some two thousand years ago?

——

Jay Hein is President at Sagamore Institute and lives in Indianapolis, Indiana, USA.

Mike Humphrey is Co-Founder at Socratic Ventures, LLC and lives in Houston, Texas, USA.

James Smith is a Consultant at 19Y Advisors and lives in Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Greg W. Spencer is CEO at Common Goods Marketplace and lives in Greensboro, North Carolina, USA.

Drayton Wade is aPrincipal at Commonwealth Ventures and lives in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, USA.

——

[1] Senor, Dan and Saul Singer, Start-Up Nation: The Story of Israel’s Economic Miracle, (New York, 2009), Hatchette Book Group Inc.

[2] https://www.oecd.org/education. Accessed Dec 1, 2020.

[3] https://tradingeconomics.com/palestine/youth-unemployment-rate. Accessed Dec 1, 2020.

[4] https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.CD?locations=PS. Accessed Dec 1, 2020.

[5] https://data.worldbank.org/country/PS. Accessed Dec 9, 2020

[6]https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2020/07/14/na071420-five-charts-that-illustrate-covid19s-impact-on-the-middle-east-and-central-asia. Accessed Dec 9, 2020.

[7] Christensen, Clayton M., Efosa Ojomo and Karen Dillon, The Prosperity Paradox: How Innovation Can Lift Nations Out Of Poverty, (New York, 2019) Harper Collins Publishing

[8] Miller, Rory, Desert Kingdoms to Global Powers: The Rise of the Arab Gulf, (Great Britain, 2016), Yale University Press

[9]https://www.businesstoday.in/sectors/it/h1b-visa-ban-infosys-ceo-salil-parekh-american-workers-hiring-us-government/story/408294.html, Accessed December 3 2020

[10]https://databank.worldbank.org/views/reports/reportwidget.aspx?Report_Name=CountryProfile&Id=b450fd57&tbar=y&dd=y&inf=n&zm=n&country=PSE, Accessed 1 January 2021

[11]https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2018/07/11/new-world-bank-report-highlights-what-it-takes-to-build-a-robust-palestinian-startup-ecosystem, Accessed Dec 28, 2020.

[12] https://www.dai.com/our-work/projects/palestine-innovative-private-sector-development-project-ipsdp, Accessed Dec 28, 2020

[13]https://www.zdnet.com/article/israel-and-palestine-how-software-developer-shortage-could-create-common-ground/ Accessed 31 October 2020

[14]https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-06-24/west-bank-property-prices-rise-as-israel-pledges-annexation, Accessed 31 October 2020

[15]https://www.hklaw.com/en/insights/publications/2020/12/israels-abraham-accords-unlocking-new-business-opportunities Accessed 29 December 2020

[16]https://www.khaleejtimes.com/business/economy/sand-curtain-has-come-down-says-ourcrowd-ceo-on-uae-israel-ties Accessed 29 December 2020

[17] Christensen, Clayton M., Efosa Ojomo and Karen Dillon, The Prosperity Paradox: How Innovation Can Lift Nations Out Of Poverty, (New York, 2019) Harper Collins Publishing

[18] Obstacles to west bank industrial development caused by the palestinian lack of control over its external and internal borders, Nunes, Aburaida 2018.

[19]Bulletin 169, Portland Trust, October 2020

[20] Miller, Rory (pg. 133)

Article originally hosted and shared with permission by The Christian Economic Forum, a global network of leaders who join together to collaborate and introduce strategic ideas for the spread of God’s economic principles and the goodness of Jesus Christ. This article was from a collection of White Papers compiled for attendees of the CEF’s Global Event.